Endometriosis is a chronic and often debilitating condition that affects millions of women and girls worldwide, yet it remains underdiagnosed and misunderstood. Imagine tissue similar to the lining of your uterus growing in places it shouldn’t—on your ovaries, fallopian tubes, or even your intestines. This misplaced tissue responds to hormonal changes just like the uterine lining does during your menstrual cycle: it thickens, breaks down, and bleeds. But unlike a normal period, this blood has nowhere to go, leading to inflammation, scarring, and excruciating pain. The World Health Organization estimates that endometriosis impacts roughly 10% of reproductive-age women and girls globally, translating to about 190 million people. In Kenya and across Africa, awareness is growing, but access to diagnosis and treatment can be challenging due to limited healthcare resources and stigma around women’s health issues.

For many, endometriosis isn’t just a medical term—it’s a daily battle. It can disrupt work, relationships, and even fertility. Symptoms often start in adolescence, but diagnosis can take years, sometimes up to a decade, because the pain is frequently dismissed as “normal” period cramps. This delay exacerbates the physical and emotional toll. Endometriosis doesn’t discriminate; it affects people of all ethnicities, though studies suggest varying prevalence rates across populations. In recent years, research has highlighted its links to immune system dysfunction and genetics, offering hope for better management.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll dive deep into what endometriosis is, its causes, symptoms, how it’s diagnosed, available treatments, and the latest breakthroughs as of 2025. Whether you’re experiencing unexplained pelvic pain, supporting a loved one, or just seeking knowledge, understanding endometriosis is the first step toward empowerment. Let’s break it down.

Understanding Endometriosis: The Basics

At its core, endometriosis occurs when endometrial-like tissue grows outside the uterus. This tissue can implant on the ovaries, forming cysts called endometriomas, or on the pelvic lining, bowels, bladder, and in rare cases, even distant sites like the lungs or brain. Unlike true endometrial tissue, which sheds during menstruation, this ectopic tissue causes internal bleeding and irritation, leading to adhesions—bands of scar tissue that can bind organs together.

The condition is estrogen-dependent, meaning it thrives in the presence of estrogen, which is why symptoms often worsen during reproductive years and may ease after menopause. However, it’s not always that straightforward; some people continue to experience pain post-menopause, especially if they’re on hormone replacement therapy.

Prevalence is staggering. Globally, it’s estimated that 1 in 10 women of reproductive age lives with endometriosis, but this could be an undercount due to diagnostic barriers. In the U.S., rates have been increasing, with a 32% rise in diagnoses from 2017 to 2024, from 24.9 to 32.8 per 10,000 patients, particularly among women aged 35-49. In Kenya, while specific data is limited, women’s health advocates report similar trends, compounded by cultural taboos around discussing menstrual health.

Endometriosis is classified into stages based on severity: minimal (Stage I), mild (II), moderate (III), and severe (IV). However, stage doesn’t always correlate with pain levels—someone with minimal disease might suffer intensely, while another with severe spread experiences mild symptoms. This unpredictability adds to the frustration for those affected.

What Causes Endometriosis?

The exact cause of endometriosis remains a mystery, but several theories have gained traction through research. One leading hypothesis is retrograde menstruation, where menstrual blood flows backward through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity instead of exiting the body. This blood may carry endometrial cells that implant and grow outside the uterus.

Another theory involves cellular transformation: peritoneal cells (lining the abdomen) may change into endometrial-like cells due to hormonal or immune factors. Embryonic cell changes during puberty, influenced by estrogen, could also play a role. Surgical scars from procedures like hysterectomies or C-sections might allow endometrial cells to attach and proliferate.

Genetics are a key factor. If your mother, sister, or aunt has endometriosis, your risk increases significantly. Immune system disorders may prevent the body from recognizing and destroying misplaced endometrial tissue. Additionally, environmental factors like exposure to toxins or high estrogen levels could contribute.

Risk factors include never having given birth, early onset of menstruation, late menopause, short menstrual cycles (less than 27 days), heavy periods lasting over seven days, low body mass index, and conditions that obstruct menstrual flow. Pregnancy and breastfeeding can temporarily alleviate symptoms by suppressing estrogen, but they’re not preventive.

Recent 2025 research points to immune-related mechanisms. Studies suggest that dysfunctional immune responses allow endometrial cells to evade destruction, leading to chronic inflammation. Big data analyses are identifying genetic markers that could predict susceptibility and guide personalized treatments. This multisystem view reframes endometriosis not just as a gynecological issue but as an inflammatory disease affecting the whole body.

Recognizing the Symptoms

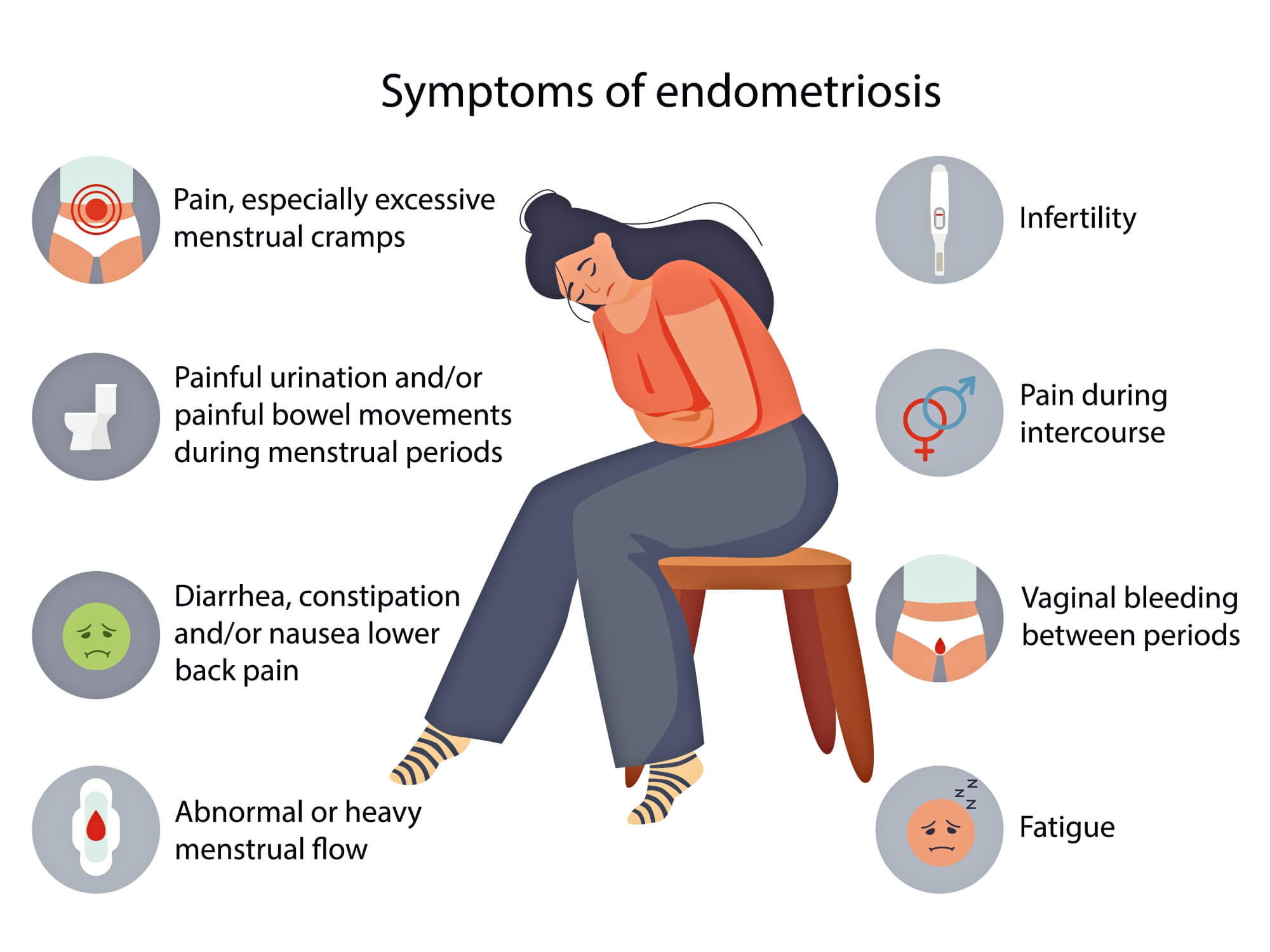

Symptoms of endometriosis vary widely, but pelvic pain is the hallmark. This isn’t your average cramp—it’s often described as sharp, stabbing, or throbbing, intensifying during periods (dysmenorrhea). Pain can radiate to the lower back, legs, or abdomen and may occur during sex (dyspareunia), bowel movements, or urination, especially around menstruation.

Other common signs include excessive bleeding—heavy periods or spotting between cycles—fatigue, bloating, nausea, diarrhea, or constipation. Infertility affects up to 50% of those with endometriosis, as scar tissue can block fallopian tubes or impair egg quality.

Mental health impacts are profound: chronic pain can lead to depression, anxiety, and isolation. Some experience “endo belly,” a swollen abdomen from inflammation. Symptoms might mimic irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or urinary tract infections, complicating diagnosis.

In adolescents, early signs like severe cramps that cause missed school days shouldn’t be ignored. Asymptomatic cases exist, discovered incidentally during fertility evaluations or surgeries.

If you’re in Kenya, cultural norms might discourage open discussion, but seeking help early is crucial. Track your symptoms in a journal—note pain intensity, cycle patterns, and triggers—to aid your doctor.

How is Endometriosis Diagnosed?

Diagnosis starts with a detailed medical history and pelvic exam, where a doctor might feel for abnormalities like cysts or scars. Imaging like ultrasound or MRI can detect endometriomas or deep lesions, but they’re not definitive for superficial endometriosis.

The gold standard is laparoscopy: a minimally invasive surgery where a camera is inserted through small abdominal incisions to visualize and biopsy tissue. This confirms the presence of endometrial-like cells histologically. However, due to risks like anesthesia, it’s not always the first step.

Diagnostic delays average 7-10 years, often because symptoms are normalized or misattributed. In 2025, emerging tools like predictive models using genetic and symptom data aim to shorten this timeline. Blood tests for biomarkers are in development but not yet standard.

If you suspect endometriosis, consult a gynecologist specializing in the condition. In Kenya, facilities like Nairobi Women’s Hospital or Aga Khan University Hospital offer expertise.

Treatment Options for Endometriosis

There’s no cure, but treatments manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Options depend on severity, age, and fertility goals.

Pain relief starts with over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen to reduce inflammation. Hormonal therapies suppress estrogen: combined oral contraceptives, progestin-only pills, IUDs, patches, or injections can lighten periods and ease pain. GnRH agonists or antagonists induce a temporary menopause-like state, but side effects like hot flashes limit long-term use.

For those planning pregnancy, hormones aren’t ideal. Surgery via laparoscopy removes lesions, adhesions, and cysts, potentially improving fertility and pain. In severe cases, hysterectomy (uterus removal) with or without oophorectomy (ovary removal) is considered, but it’s not always curative if tissue remains elsewhere.

Complementary approaches include physiotherapy for pelvic floor dysfunction, acupuncture, or dietary changes like anti-inflammatory foods. Fertility treatments like IUI or IVF help those struggling to conceive.

2025 advancements include non-hormonal drugs targeting immune pathways. Research at Michigan State University is progressing toward novel therapies that address pain without affecting hormones. Pipeline drugs focus on reducing inflammation and preventing lesion recurrence.

In Kenya, access varies; public hospitals may offer basic care, while private ones provide advanced surgery. Cost and availability are barriers, so advocacy groups like Endometriosis Foundation of Kenya can connect you to resources.

Latest Research on Endometriosis in 2025

Research is accelerating. Big data from UCSF is uncovering genetic clues, potentially leading to non-invasive diagnostics and targeted therapies. Immune studies suggest new drug targets, like modulating macrophages to halt lesion growth.

A 25-year review highlights progress in understanding endometriosis as multisystem, informing symptom management beyond hormones. Diagnostic innovations include AI models predicting risk from health records. Prevalence is rising, urging more funding.

In Australia, researchers at Hudson Institute are answering key questions on fertility and pain relief. Globally, calls for action emphasize inclusive trials and affordable treatments.

Living with Endometriosis

Coping involves a holistic approach: build a support network, join groups, and prioritize self-care. Exercise, yoga, and mindfulness reduce stress. Track flares and adjust lifestyle—avoid triggers like caffeine.

Work accommodations, like flexible hours, help manage fatigue. For fertility, early consultation is key. Mental health support is vital; therapy addresses the emotional burden.

In Kenya, community awareness campaigns are empowering women to seek care without shame.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is more than pain—it’s a call for better healthcare and understanding. With early diagnosis and tailored treatments, many lead fulfilling lives. If symptoms resonate, consult a professional. Together, we can destigmatize this condition and advocate for change.